Once upon a time, fairy tales were dark fables designed to scare children into good behavior. This is the story of one American author who thought kids deserved better.

Once upon a time, fairy tales were dark fables designed to scare children into good behavior. This is the story of one American author who thought kids deserved better.

In December 1900, L. Frank Baum was a struggling, 44-year-old writer living in Chicago with his wife and four children. Christmas was only days away, and Baum was desperately searching for a way to buy presents for his family.

On a whim, Baum went downtown to ask his publisher for a royalties’ advance for the five books he’d written that year. He walked out with a check for one of the books, and promptly stuck it in his pocket. He didn’t bother to take a look at it.

When Baum arrived home, his wife, Maud, was ironing a shirt. He reluctantly handed her the check, and at the same moment, they both discovered that it was for $1,423.98—roughly $40,000 today. Paralyzed with disbelief, Maud burned a hole through the shirt.

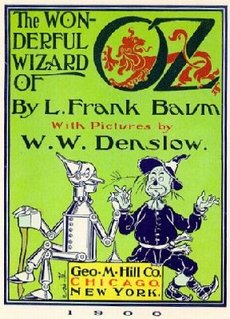

That book, of course, was The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

THE MAN BEHIND THE CURTAIN

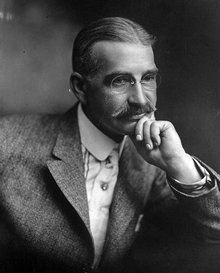

Lyman Frank Baum was born in 1856 in Chittenango, New York. As a child, his weak heart limited his capacity for rough-and-tumble play. So, despite being the seventh of nine kids, he spent most of his childhood alone, indoors, and dreaming.

Lyman Frank Baum was born in 1856 in Chittenango, New York. As a child, his weak heart limited his capacity for rough-and-tumble play. So, despite being the seventh of nine kids, he spent most of his childhood alone, indoors, and dreaming.

As a young man, Baum leapt like a flea from career to career. By his early 30s, he’d been a journalist, a printer, a postage-stamp dealer, and a champion poultry breeder, which led him into publishing, with his trade journal The Poultry Record. He also ran his own theater company, where he wrote, directed, and acted in his own plays.

Then, in 1881, Baum met his leading lady—Maud Gage, a sophomore at Cornell. But Maud’s mother, Matilda, disapproved of the union. Matilda Gage was a feminist who marched alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in the women’s suffrage movement. She saw Baum as a flake who’d never amount to anything, and she told her daughter she’d be a “darned fool” to marry the itinerant actor. Yet, Baum’s charm, sincerity, and uncanny ability to tell fantastic stories were no match for Matilda, and he soon won her over. He also became a feminist.

Frank married Maud in 1882, but troubles were around the corner. Baum’s theater company went belly-up, and without local prospects, he looked west for opportunity. In 1888, he moved his family to the Dakota Territory, where he opened a store in the town of Aberdeen. (Years later, when Baum wrote descriptions of the Kansas prairie in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, he was actually describing South Dakota.) His shop, Baum’s Bazaar, sold Chinese paper lanterns, Bohemian glass, gourmet chocolates, and other exotic items. But Baum overestimated the frontier’s demands for novelty shopping. In a few short years, he’d gone bust yet again.

Frank married Maud in 1882, but troubles were around the corner. Baum’s theater company went belly-up, and without local prospects, he looked west for opportunity. In 1888, he moved his family to the Dakota Territory, where he opened a store in the town of Aberdeen. (Years later, when Baum wrote descriptions of the Kansas prairie in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, he was actually describing South Dakota.) His shop, Baum’s Bazaar, sold Chinese paper lanterns, Bohemian glass, gourmet chocolates, and other exotic items. But Baum overestimated the frontier’s demands for novelty shopping. In a few short years, he’d gone bust yet again.

At this point, L. Frank Baum was 35 with no career. He headed east for Chicago, where he received guidance from an unexpected source: his mother-in-law. Matilda Gage convinced Baum to pursue his one true talent, telling stories. In Aberdeen, children had stalked Baum, demanding story hour from the raconteur. Kids loved his tales because they weren’t thinly disguised morality lessons. Instead, Baum’s stories were fantasies filled with candy, toys, magic, and adventure. Heeding Matilda’s advice, Baum decided to give writing a try.

FOLLOWING THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD

In 1899, Baum teamed up with illustrator W.W. Denslow and published Father Goose, His Book, a collection of pictures and verse. The collaboration worked so well that it inspired Baum and Denslow to try their hands at a full-length novel.

As a child, Baum had loved the European fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, but he loathed the dark, grisly endings. He envisioned a new American fairy tale in which ingenuity and spunk paid off. In Baum’s words, he wanted to create a world where “wonderment and joy are retained, and the heartache and nightmares left out.”

As a child, Baum had loved the European fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, but he loathed the dark, grisly endings. He envisioned a new American fairy tale in which ingenuity and spunk paid off. In Baum’s words, he wanted to create a world where “wonderment and joy are retained, and the heartache and nightmares left out.”

It was a great idea, but what would he call this utopia? Family legend holds that Baum scanned his office for ideas. While staring at his filing cabinet, he drew inspiration from a label on the bottom drawer marked “O-Z.”

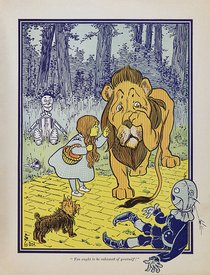

Baum’s book was turned down by every major publishing house. Finally, a distribution company agreed to take on the novel about Oz, but only if Baum and Denslow agreed to shoulder the printing expenses. The bet paid off. Today, the masterful integration of color illustrations and text is heralded as a pioneering achievement in literature, a precursor to the graphic novel. Denslow’s drawings were unique in that they not only reflected the plot, but also furthered it. His vibrant pictures spilled over from one page to the next.

More importantly, children loved Baum’s story. By the end of 1900, Maude had burned a hole through her husband’s shirt, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was the best-selling book in America.

OZ FEST

Over the next 20 years, Baum would pen more than 70 books under several pseudonyms. Unfettered by gender restrictions, he often wrote under female names, including Suzanne Metcalf, Laura Bancroft, and Edith Van Dyne. Baum also tried his hand at science-fiction, demonstrating a knack for predicting the future on par with H.G. Wells. A running theme in Baum’s work was the triumph of technology over distance and time, and many of his fictional inventions—televisions, satellites, cell phones, laptops—eventually became realities of everyday life.

In 1902, Oz was transformed into a Broadway musical, shortened simply to The Wizard of Oz.

In 1902, Oz was transformed into a Broadway musical, shortened simply to The Wizard of Oz.

At first, Baum was taken aback by some of the changes. For instance, Dorothy’s faithful companion on the stage wasn’t Toto, but a cow named Imogene.

But when the play became a Broadway hit, Baum softened. He tried to return to the theater to produce his own plays, but all his efforts, including The Whatnexters and The King of Gee Whiz, were flops. He also tried his hand at a vaudeville show, “Fairylogues and Radio Plays,” but that foundered, too.

The truth was that Baum wanted to stop writing about Dorothy and do something new. He intended for the sixth Oz book, The Emerald City of Oz, to be the last in the series. In the story, Baum seals off his fairyland, proclaiming it unreachable from the outside world. But when a film project he was pursuing collapsed, Baum quickly found himself strapped for funds again. He wrote another Oz book, and from then on, Dorothy and the gang kept resurfacing every time Baum needed to pad his wallet.

IT’S A TWISTER

In 1919, Baum died of the same heart condition that had kept him indoors as a child. But even death couldn’t stop the Oz stories from flowing. Baum wrote the 14th book in the series, Glinda of Oz, on his deathbed, and it was published posthumously. After that, various authors churned out 26 official sequels, which have been translated into 22 languages, from Tamil to Serbo-Croatian.

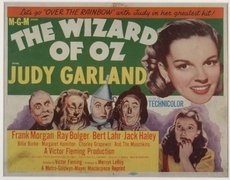

In 1939, the Oz legacy hit a turning point when MGM released The Wizard of Oz movie. Based on Baum’s original storyline, the plot and characters remained relatively faithful to the book, although there were plenty of changes, too. Most of the quotables (“And your little dog, too!”) were Hollywood additions, as were the musical numbers and dancing little people. There were some changes to the story, as well. Dorothy’s slippers, which were silver in the book, were changed to ruby in the movie to show off the new technology of color film.

In 1939, the Oz legacy hit a turning point when MGM released The Wizard of Oz movie. Based on Baum’s original storyline, the plot and characters remained relatively faithful to the book, although there were plenty of changes, too. Most of the quotables (“And your little dog, too!”) were Hollywood additions, as were the musical numbers and dancing little people. There were some changes to the story, as well. Dorothy’s slippers, which were silver in the book, were changed to ruby in the movie to show off the new technology of color film.

The key difference between the two versions is that in the movie, Dorothy’s adventure was “all a dream,” while in Baum’s book, Oz was very much real. In fact, later in the book series, Uncle Henry and Auntie Em move to the Emerald City to dine off jeweled plates and converse with talking animals. As it turned out, nobody really wanted to go home to Kansas.

(Image from the NeatoShop)

(Image from the NeatoShop)

The movie established Dorothy, the Tin Man, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion as cultural icons. Flying monkeys and yellow brick roads became part of the national psyche, and today, Oz’s popularity shows no sign of waning. The movies, the spin-offs, the Broadway musicals, the plays, and—more recently—the pop-up book just keep cropping up. Much like Dorothy and the gang, Baum took the long way to finding his true calling, but there’s no denying that he left behind an enduring legacy. By writing the quintessential American fairy tale, Baum proved that even late bloomers living in their own fantasy world are entitled to happy endings.

__________________________

The article by Kelly K. Ferguson is reprinted from the May- June 2010 issue of mental_floss magazine.

The article by Kelly K. Ferguson is reprinted from the May- June 2010 issue of mental_floss magazine.

Be sure to visit mental_floss‘ website and blog for more fun stuff!

![]()

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário