John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

I was wrong.

Not about the implosion of the credit markets, which I urgently warned about in 2007 and early 2008. Not about the recession, which we shifted to anticipating in November 2007. Not about the plunge in the stock market, which erased the entire 2002-2007 market gain, which was no surprise. Not about the "ebb and flow" of short-term data, which I frequently noted could produce a powerful (though perhaps abruptly terminated) market advance even in the face of dangerous longer-term cross-currents. I expect not even about the "surprising" second wave of credit distress that we can expect as we move into 2010.

From a long-term perspective, my record is very comfortable. But clearly, I was wrong about the

extent to which Wall Street would respond to the ebb-and-flow in the economic data – particularly the obvious and temporary lull in the mortgage reset schedule between March and November 2009 – and drive stocks to the point where they are not only overvalued again, but strikingly dependent on a sustained economic recovery and the achievement and maintenance of record profit margins in the years ahead.

I should have assumed that Wall Street's tendency toward reckless myopia – ingrained over the past decade – would return at the first sign of even temporary stability. The eagerness of investors to chase prevailing trends, and their unwillingness to concern themselves with

predictable longer-term risks, drove a successive series of speculative advances and crashes during the past decade – the dot-com bubble, the tech bubble, the mortgage bubble, the private-equity bubble, and the commodities bubble. And here we are again.

We face two possible states of the world. One is a world in which our economic problems are largely solved, profits are on the mend, and things will soon be back to normal, except for a lot of unemployed people whose fate is, let's face it, of no concern to Wall Street. The other is a world that has enjoyed a brief intermission prior to a terrific second act in which an even larger share of credit losses will be taken, and in which the range of policy choices will be more restricted because we've already issued more government liabilities than a banana republic, and will steeply debase our currency if we do it again. It is not at all clear that the recent data have removed any uncertainty as to which world we are in.

Taking the weighted average

outcome for the two states of the world still produces a poor average return/risk tradeoff. Taking the weighted average

investment position for the two states of the world is somewhat more constructive. As I noted several weeks ago, I have adapted our weightings accordingly. As a result, we have been trading around a modest positive net exposure, increasing it slightly on market weakness, and clipping it on strength, as is our discipline. Currently, the Strategic Growth Fund has a net exposure to market fluctuations of less than 10%, but enough "curvature" (through index options) that our exposure to market risk will automatically become more muted on market weakness and more positive on market advances, allowing us to buy weakness and sell strength without material concern about the (increasing) risk of a market collapse.

There is no chance, even in hindsight ("could have, would have, should have" stuff) that I would have responded to the existing evidence in recent months with more than a moderate exposure to market risk during some portion of the advance since March. But our year-to-date returns might now be into a second digit had I recognized that investors have learned utterly nothing from the bubbles and collapses of the past decade. That recognition might have encouraged a greater weight on trend-following measures versus fundamentals, valuations, price-volume sponsorship, and other factors.

Still, our stock selections continue to perform well relative to the market, our risks remain well-managed through a substantial (though not full) hedge, and our investment approach has nicely outperformed the S&P 500 over complete market cycles, with substantially less downside risk than a passive investment approach. We have implemented some modest changes to improve our potential to benefit from (even ill-advised) speculative runs, but we've done fine nonetheless, and we can sleep nights.

Whether or not I have focused too much on probable "second-wave" credit risks is something we will find out in the quarters ahead – my record of economic analysis is strong enough that a "miss" on that front would be an outlier. What I do think is that over the past decade, investors (including people who hold themselves out as investment professionals) have become far more susceptible to reckless myopia than I would have liked to believe. They have become speculators up to the point of disaster.

Frankly, I've come to believe that the markets are no longer reliable or sound discounting mechanisms. The repeated cycle of bubbles and

predictable crashes over the recent decade makes that clear. Rather, investors appear to respond to emerging risks no more than about three months ahead of time. Worse, far too many analysts and strategists appear to discount the future only in the most pedestrian way, by taking year-ahead earnings estimates at face value, and mindlessly applying some arbitrary and historically inconsistent multiple to them.

This is utterly different from true discounting – which

does not rely on multiples, but instead carefully traces out the likely path of future revenues, profit margins, cash flows and earnings over time, and explicitly discounts expected payouts and probable terminal values back at an appropriate rate of return. That's what we actually do here. Talking in terms of multiples can make the process easier to explain, and can be a reasonable approach to the market as a whole if earnings are normalized properly, but ultimately, an investment security is a claim to a

long-term stream of cash flows. It is not simply a blind multiple to the latest analyst estimate.

Fortunately, the evidence suggests that the long-term returns to a careful discounting approach tend to be strong even if investors repeatedly behave in speculative and short-sighted ways. This is because

long-term returns are

fully determined by the stream of cash flows actually received by investors over time, and because inappropriate valuations ultimately tend to mean-revert. In the face of speculative noise, the long-term returns from a proper discounting approach may not capture as much speculative return as might be possible, but over time, many of those speculative swings tend to wash out anyway.

In part, the market's increasing propensity toward speculation reflects the increasing lack of fiscal and monetary discipline from our leaders. Policy makers who seek quick fixes and could care less about long-term consequences undoubtedly encourage investors to embrace the same value system. Paul Volcker was the last Fed Chairman to have any sense that discipline and the acceptance of temporary discomfort was good for the nation.

Our current Fed Chairman's voice literally quivers in response to the phrase "bank failure," even though in the present context, a bank failure implies none of the disorganized outcomes that characterized the Great Depression. It simply means that the bondholders take a loss and the remaining part of the institution survives intact as a "whole bank" entity (and can be sold or re-issued back to public ownership, less the debt to bondholders, as such). The same outcome would have been possible with Lehman had the FDIC been granted authority from Congress to take conservatorship of a non-bank financial entity.

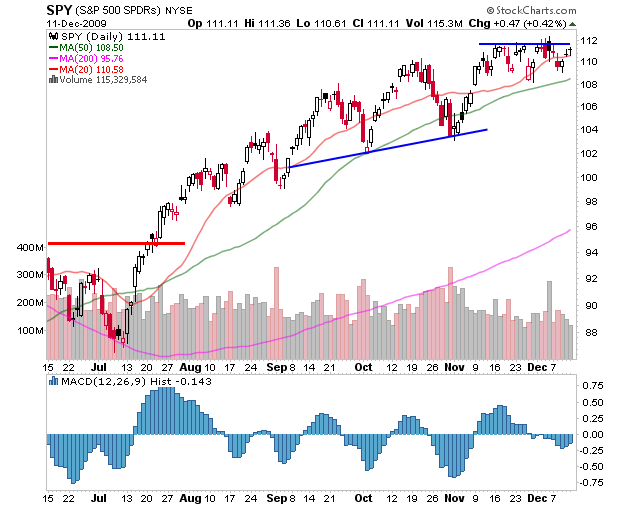

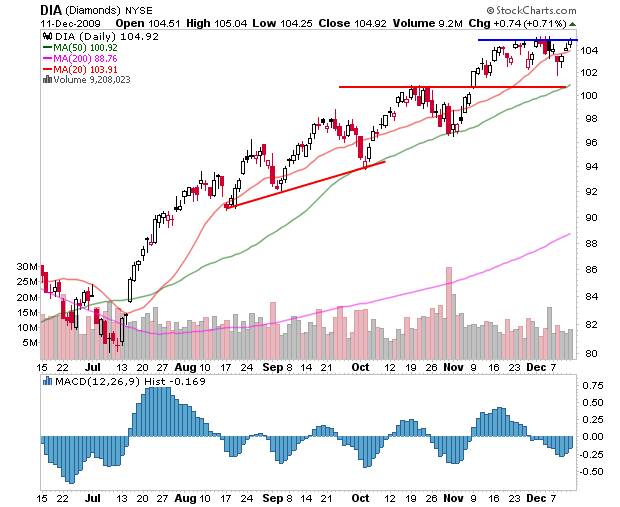

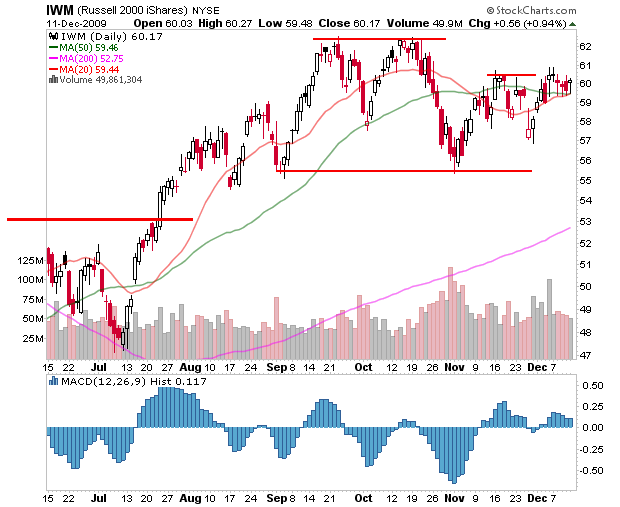

In my estimation, there is still close to an 80% probability (Bayes' Rule) that a second market plunge and economic downturn will unfold during the coming year. This is not certainty, but the evidence that we've observed in the equity market, labor market, and credit markets to-date is simply much more consistent with the recent advance being a component of a more drawn-out and painful deleveraging cycle. Meanwhile, valuations are clearly unfavorable here, and even under the "typical post-war recovery" scenario, we are observing an increasing number of internal divergences and non-confirmations in market action.

As Gluskin Sheff chief economist David Rosenberg noted last week, "Even if the recession is over, the historical record shows that downturns induced by asset deflation and credit contraction are different than a garden-variety recession induced by Fed tightening and excessive manufacturing inventories since the former typically induce a secular shift in behavior and attitudes towards debt, asset allocation, savings, discretionary spending and homeownership. The latter fades more quickly.

"This is why people didn't figure out that it was the Great Depression until two years after the worst point in the crisis in the 1930s; and why it took decades, not months, quarters or even years, for the complete transition to the next sustainable economic expansion and bull market.

"Mortgage applications for new home purchases hit a 12-year low in the middle of November (down 22% in the past month!), fully two weeks after the Administration said it was going to not only extend but expand the program to include higher-income trade-up buyers. Once again, there is minimal demand for autos and housing, and that is partly because the market is still saturated with both of these credit-sensitive big-ticket items after an unprecedented credit and consumer bubble that went absolutely parabolic in the seven years prior to the collapse in the financial markets an asset values. We are probably not even one-third of the way through this deleveraging cycle. Tread carefully."

Andrew Smithers, one of the few other analysts who foresaw the credit implosion and remains a credible voice now, concurred last week in an interview with my friend Kate Welling (a former Barrons' editor now at Weeden & Company): "The good news so far is that the stock market got down to pretty much fair value or even, possibly, a tickle below it, at its March bottom. But now it has gone up… we probably have a market which is, roughly, 40% overpriced. In order to assess value, it is necessary either to calculate the level at which the EPS would be if profits were neither depressed nor elevated, or to use a metric of value which does not depend on profits. The cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) normalizes EPS by averaging them over 10 years. It thus follows the first of those two possible methods. Using even longer time periods has advantages, particularly as EPS have been exceptionally volatile in recent years - and using longer time periods raises the current measured degree of overvaluation. The other methodology we use measures stock market value without reference to profits: the q ratio. It compares the market capitalization of companies with their net worth, also adjusted to current prices. The validity of both of these approaches can be tested and is robust under testing - and they produce results that agree. Currently, both q and CAPE are saying that the U.S. stock market is about 40% overvalued."

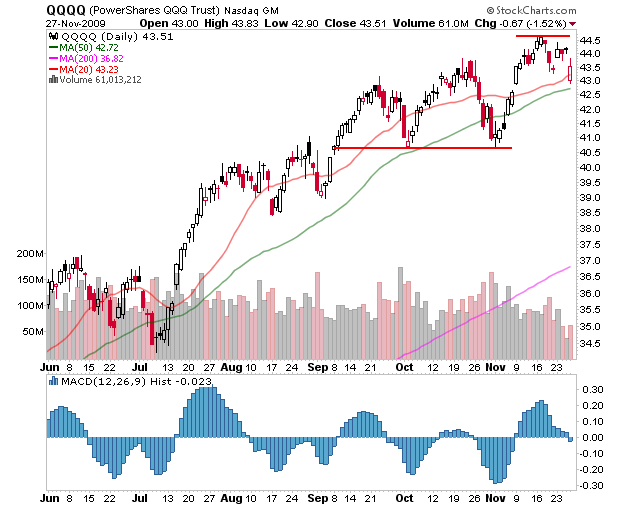

In the chart below, the current data point would be about 0.4, not as extreme as we observed in 1929, 2000, or 2007 of course, but equal to or beyond what we've observed at virtually every other market peak in history. This aligns well with our own analysis, where as I've noted in recent weeks, the S&P 500 is priced to deliver one of the weakest 10-year total returns in history except for the (ultimately disappointing) period since the mid-1990's.

One of the fascinating aspects of the past few months is the lack of equilibrium thinking with respect to what happened to the trillions of dollars in government money that has been spent to defend the bondholders of mismanaged financial companies. Almost by definition, money given to corporations will show up most quickly as improvements in corporate earnings, and then slightly later, as executive compensation. A few pieces came across my desk last week, hailing the ability of the corporate sector to bounce back from the recent economic downturn even though revenues have continued to suffer and employment has been steeply cut. Why is this a surprise? Where else could the money have gone? Labor compensation? It is truly mind-numbing that a moment after a temporary surge of

trillions of dollars, borrowed and tossed out of a helicopter (though to specific corporations and private beneficiaries), analysts would hail a subsequent improvement in corporate results as evidence of "resilience."

What matters is sustainability, and unfortunately, it is clear that credit continues to collapse. Banks are contracting their loan portfolios at a record rate, according to the latest FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile. Even so, new delinquencies continue to accelerate faster than loan loss reserves. Tier 1 capital looked quite good last quarter, as one would expect from the combination of a large new issuance of bank securities, combined with an easing of accounting rules to allow "substantial discretion" with respect to credit losses. The list of problem institutions is still rising exponentially. Overall, earnings and capital ratios have enjoyed a reprieve in the past couple of quarters, but delinquencies have not, and all evidence points to an acceleration as we move into 2010.

Urgent Policy Implications

From a policy standpoint, it is effectively too late to forestall further foreclosures absent explicit losses to creditors. The best policy option now is to make sure that the second wave does not result in a debasement of the U.S. dollar. The way to do that is to require three things:

First, the FDIC should be given regulatory authority to take non-bank financials into conservatorship the way they should have been able to do with Bear Stearns and Lehman. If this authority had existed in 2008, Bear's bondholders would not now stand to get 100% of their money back, with interest, as they presently do, and Lehman's disorganized liquidation would have been completely unnecessary. As I've noted before, the problem with Lehman was not that it went bankrupt, but that it went bankrupt in a

disorganized way. If the FDIC had authority over insolvent non-bank financials and bank holding companies, it could wipe out equity and an appropriate amount of bondholder capital, and sell the fully-functioning residual to an acquirer, as is typically done with failing banks, without any loss to depositors or customers.

Second, bank capital requirements should be altered to require a substantial portion of bank debt to be of a form that

automatically converts to equity in the event of capital inadequacy. This would force losses onto bondholders, rather than onto taxpayers. This policy adjustment is urgent – we have perhaps a few months to get this right.

Finally, Congress should be clear that government funds will be available only to protect the interests of depositors, not bondholders. Specifically, any funds provided by the government should be contingent on the ability to exert a senior claim to bondholders in the event of subsequent bankruptcy, even if a category is created to allow those funds to be counted as "capital" for purposes of satisfying capital requirements prior to such bankruptcy. Government-provided capital should be subordinate

only to depositor claims, if equity and bondholder capital ultimately proves insufficient to meet those obligations.

Since early 2008, beginning with the provision of non-recourse funding in the Bear Stearns debacle, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury have repeatedly allocated or implicitly obligated public funds to defend the bondholders of mismanaged financial companies. This has included the outright and non-recourse purchase of nearly a trillion dollars in mortgage securities that have no explicit guarantee by the U.S. government. By purchasing these securities outright (rather than through a well-defined repurchase agreement), the Fed is effectively obligating the U.S. government to either guarantee them or to absorb any future losses.

Aside from the fraction of bailout funding that was specifically allocated by Congress through legislation, these actions represent an unconstitutional breach into enumerated spending powers that are the domain of the elected members of Congress alone. The issue here is not whether the Fed should be independent from political influence. The issue is the constitutionality of the Fed's actions. The discretion that it has exerted over the past two years crosses the line into prerogatives reserved for Congress. That line needs to be clarified sooner rather than later.

Emphatically, the trillions of dollars spent over the past year were

not in the interest of protecting bank depositors or the general public. They went to protect bank bondholders. Instead of taking appropriate losses on those bonds (which financed reckless mortgage lending), those bonds are happily priced near their face value, for the benefit of private individuals, thanks to an equivalent issuance of U.S. Treasury debt. But that's not enough. Outside of a very narrow set of institutions that are subject to compensation limits, just watch how much of the public's money – which benefitted several major investment banks following a very direct route – gets allocated to Wall Street bonuses in the next few weeks.

John F. Mauldin

johnmauldin@investorsinsight.com